States’ Deployment of Short-Term Funding in Home- and Community-Based Services Exposes Need for Longer-Term Investments

Highlighting the Urgent Need for Sustainable Investments in HCBS for Seniors

December 19, 2022Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) is a critical system for serving low-income seniors and allowing them to age at home rather than in congregate care facilities like nursing homes. Despite the vital role that Medicaid HCBS plays in ensuring that some of the most vulnerable populations are able to receive quality care in their preferred setting, HCBS has been historically underfunded with long wait times. In 2021, states received a rare opportunity to boost resources for these critical services for elderly and disabled populations when President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 into law. ARPA included a wide- ranging set of policies and funding, including $12.7 billion made available to state Medicaid programs, according to Congressional Budget Office. This funding was intended to address the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the disruption to the economy.

States took advantage of this opportunity to strengthen their Medicaid HCBS systems and offer relief to providers who have faced significant challenges as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, analysis of state HCBS plans show that states have used the funds to provide additional payment for the direct care workforce, invest in workforce training and recruitment and retention initiatives, make technological and infrastructure improvements (including access to telehealth), offer additional services such as caregiver supports, invest in quality improvement programs, and explore opportunities to address housing and other social determinants of health.

While these investments will bolster current HCBS systems as they recover from COVID-19, the short-term nature of the ARPA funding have meant that states have not used the dollars to make more transformational changes that would address more longstanding deficiencies in care for older adults and those with disabilities, allowing more individuals to age at home. While substantial funding for HCBS was included in the Build Back Better Act in 2021, it was ultimately left out of the Inflation Reduction Act when it was passed in August 2022. In order to meet the critical needs of this system, more long-term investment is needed in Medicaid HCBS.

Medicaid HCBS Helps Older Adults Stay in Their Homes, But State Resources Are Limited

Medicaid HCBS is a critical tool for states to allow individuals to live in their homes and get the services they need in the community as opposed to moving into a nursing facility or other congregate care setting. Examples of these services include visits from home health aides, assistance with self-care tasks such as eating or bathing, preparing and taking medication, case management, housing and meal supports, and payments to family members who act as caregivers. People who use HCBS are predominantly older adults with physical and/ or cognitive limitations as well as individuals with intellectual or physical disabilities.

In the past decade, states have significantly increased the proportion of long-term care spending from congregate care settings to HCBS. In 2016, states spent a total of $95 billion on HCBS, compared with about

$67.1 billion on institutional services. Despite the increase, states have struggled with high levels of unmet needs and lack of adequate funding for HCBS since long before the COVID-19 pandemic began. In February 2020, approximately 820,000 people were on state waiting lists to receive Medicaid HCBS, with an average wait time of 39 months. The direct care workforce who provide HCBS has a very high staff turnover rate, as the workers, who are predominantly women of color, are paid low wages with minimal opportunity for career advancement.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted how critical it is to offer services that allow people to age comfortably in their homes. Individuals in congregate care settings and those who serve them have been some of the populations most profoundly impacted by the pandemic. As of February 2022, 200,000 residents and staff of long-term care facilities have died due to COVID-19, which is 23% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States. This has further exacerbated the many challenges around unmet need, funding, and burnout that individuals who receive long-term services and their care providers already face prior to the pandemic.

American Rescue Plan Act Funding Provides One-Time Support for HCBS

The American Rescue Plan Act provides $12.7 billion new federal dollars to states for HCBS through a 10% increase to the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) through March 31, 2022. States must use the additional funding to invest directly in activities that enhance, expand, or strengthen HCBS and are able to spend any new funding that they draw down through the opportunity through March 31, 2025. To receive the increased funding, states were required to submit spending plans for approval for how they intend to use the funding to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

States Are Using ARPA Funds to Make Short-Term Investments in HCBS

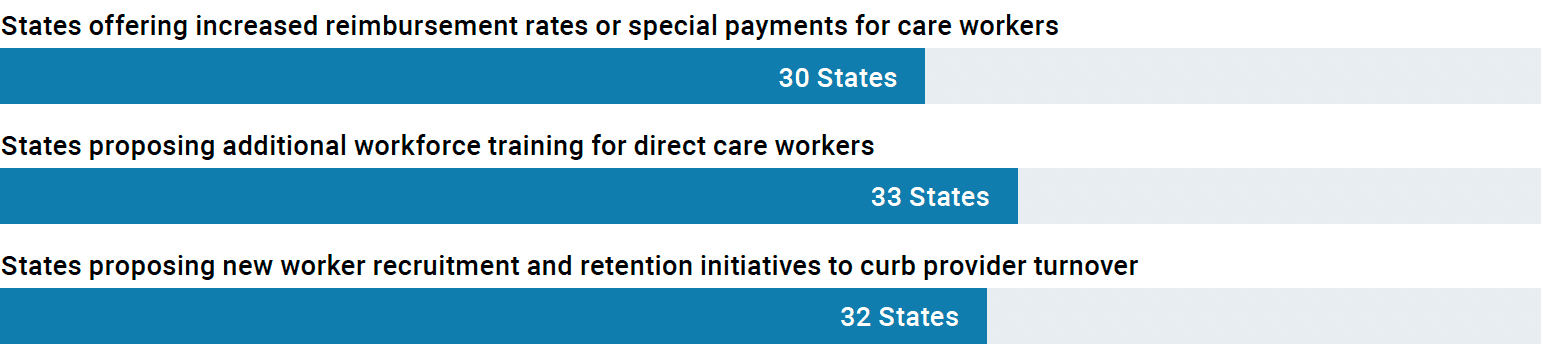

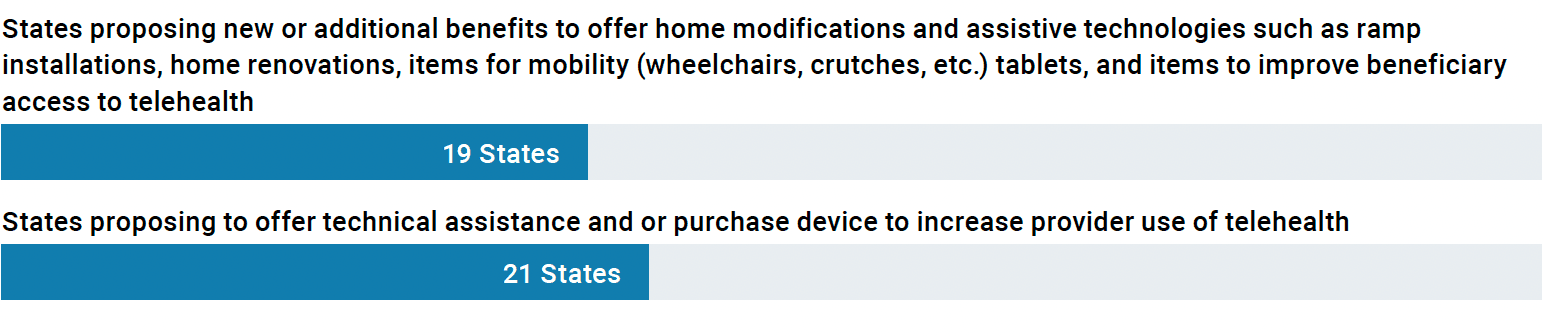

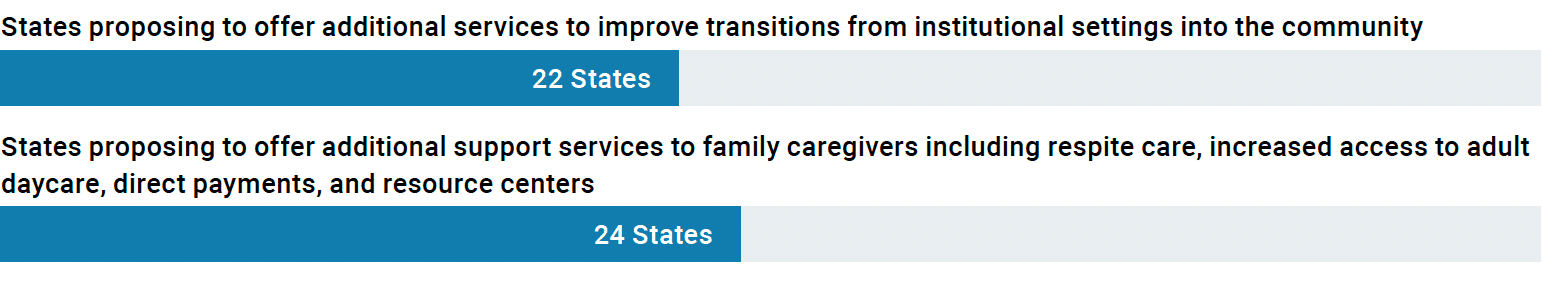

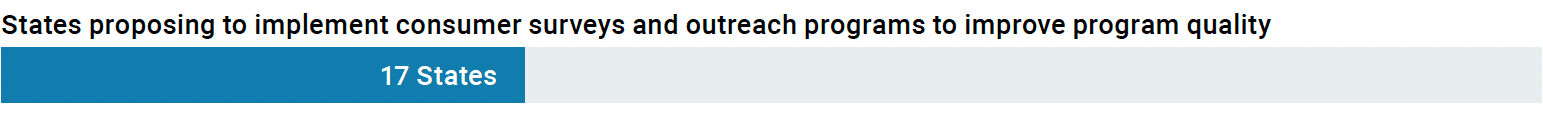

West Health’s analysis of the ARPA HCBS spending plans reveals that states are using this one-time federal funding to enhance, expand, and strengthen Medicaid home- and community-based services. As of September 2021, all 50 states and the District of Columbia have submitted at least an initial spending plan to CMS. States have focused their funding efforts on supporting the HCBS workforce through increased investments in healthcare providers and in technology to improve access to services. The most common areas of investment include:

Workforce Investments: Workforce investments offered under state HCBS spending plans are intended to bolster the HCBS workforce by offering increased payment, training, career advancement opportunities, and certifications to recruit new workers into the HCBS workforce.

Technological and Infrastructure Improvements: The technological and infrastructure improvement components of state HCBS plans include one-time improvements and assistive technologies for Medicaid HCBS beneficiaries as well as improvements and technical assistance for providers to improve utilization of telehealth.

Additional Services for Beneficiaries and Caregivers: A number of states used the increased funding to add entirely new services or expand eligibility for existing services to improve care for individuals who receive HCBS. Examples of new investments include home-delivered meals, additional behavioral health benefits for certain populations, transportation, and housing and tenancy supports. States also included new services and supports for family caregivers, who have been strained during the pandemic.

Quality Improvement: States also included quality improvement initiatives under their state plans, including consumer surveys, outreach and engagement programs, and new quality measures in order to better understand and improve how care is being delivered through the state HCBS program.

A Case Study: California’s Master Plan for Aging Helps to Better Allocate Federal Funding

ARPA’s HCBS funding presented states with a rare opportunity to leverage significant amounts of new federal funds in order improve crucial, but historically underfunded programs. Given the short- term nature of the ARPA funding availability, states needed to respond quickly to CMS in order to draw down available funding. Long-term, cross-agency strategic planning, such as a Multi-Sector Plan for Aging, can help states respond nimbly to new funding opportunities and to use those opportunities efficiently to target areas where funding is most needed.

A Multi-Sector Plan for Aging is a long-term blueprint to connect the public and private sectors for the purpose of restructuring of state and local policy, programs, and funding toward aging well in the community, touching health, human services, housing, transportation, employment, and many other areas. California’s Master Plan for Aging was released in January 2021, following an executive order by Governor Gavin Newsom. Through the development process, a robust group of stakeholders in California, including the Governor’s office, legislature, and state agencies agreed upon cross-cutting goals and initiatives to address key issues related to aging and budgetary actions back to those goals. This put California in a position to quickly translate the goals and initiatives included in the Master Plan for Aging into the California HCBS Spending Plan with an understanding that there was already senior leadership buy in for these initiatives.

In its annual report, California identified that HCBS spending plan dollars were used by the state to implement a plan for a nutrition support initiative, increase options for housing supports, develop new dementia screening practices, increase transparency on state nursing home data, provide new devices and training for older adults to close the digital divide. All of these activities are very closely related to the state’s overall aging goals as articulated by the state’s Master Plan.

States Need Longer-Term HCBS Investment and Planning

ARPA funding has allowed states to make a number of one-time improvements that will help to bolster the strained HCBS workforce and improve services that are critical for older adults to continue to live in the community. But because the funding offered under the ARPA is time limited, as states have only 1 year to draw down the matching dollars, many of the improvements made by the states are either short-term (e.g. Special payments to providers, funding for training programs) or one-time investments (e.g. Technological improvements). This one-time funding opportunity is insufficient to allow for long-term improvements that have been needed to improve access to HCBS since before the pandemic began. HCBS will only continue to become more important to our national health care system as by 2030, one in four people will be 65 or older.

Longer-term planning by states, such as through a cross-sector plan for aging, can allow states to be more forward thinking in their HCBS investments, allowing them to focus, for example, on services that impact the social determinants of health. The master plan for aging process also allows a state Medicaid agency to move forward with buy in from senior state leadership, allowing them to be nimbler when the opportunity for increased funding does arise.

There has been momentum in the last year to increase federal funding for HCBS. The version of the Build Back Better Act that was passed by the House of Representatives included $150 billion in additional funding for HCBS over 10 years, though the bill ultimately did not pass. Critically, HCBS funding was not included in the Inflation Reduction Act when it was passed by Congress in August 2022. Many advocates estimate it would take at least $250 billion to clear the waiting lists for care and services alone and more investment is needed in order to realize the opportunity to improve the lives of older adults and individuals with disabilities by allowing more individuals to live, age, and thrive in the community, a desire of the overwhelming majority of adults in America. As Congress and the Administration look towards priorities for an end-of-year package, they should consider the needs of the HCBS system, providing not only sufficient funding, but also ensure that the funding is provided in a way that offers a true opportunity to transform the way that care is delivered for older adults and individuals with disabilities.

About West Health Policy Center

Based in the nation’s capital, the West Health Policy Center conducts policy research, education, and outreach on a range of issues including healthcare costs and prescription drug pricing, value-based care models, and senior-specific models of care. The goal is to connect best practices to policies that increase access, lower costs, and improve care.

Downloads

WH-Issue-Brief-12-19-22-1.pdf

Download