Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reforms: Can Congress Fix the Market Without Breaking It?

This research was informed by a confidential roundtable and interviews with industry stakeholders. West Health and ATI Advisory gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Amy Herr, William Scanlon, and Marta Wosinska.

April 17, 2024Introduction

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) play a central role in determining access and spending for prescription drugs in the United States. PBMs earn revenues from negotiating price and payment concessions from pharmaceutical companies and pharmacies on behalf of health plans. This arrangement encourages them to control prescription drug prices and spending, but has recently become controversial. Multiple stakeholders argue that PBMs use their market power to serve their own interests over those of health plans and their beneficiaries. Others assert that PBMs, under common ownership with pharmacies and health plans, disadvantage their unaffiliated rivals in these markets.

In Congress, proposals to reform the PBM business model have become one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement. Most center on regulating how PBMs earn money. Legislation to this effect raises questions about whether lawmakers can ensure that PBMs use their market power on behalf of health plans and beneficiaries without sacrificing their motivation to control prescription drug costs.

A definitive answer will have to wait. Congress appears unlikely to pass any PBM reforms before the 2024 election season concludes. In the meantime, political pressure continues to build. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is running an ongoing investigation, and the White House has placed significant attention on the issue. Once Congress returns to the topic, the reforms that have passed committee will serve as the basis for a negotiated consensus package.

To understand the potential impact of an eventual PBM reform package, we examine the underlying issues current proposals aim to address, as well as which types of plan sponsors and beneficiaries are most affected by them. We go on to consider whether proposed reforms can achieve their aims without sacrificing PBMs’ incentive and ability to negotiate. Finally, we identify modifications that could improve this tradeoff.

Background

Many high-income countries take a centralized approach to negotiating drug prices and setting reimbursement benchmarks for the supply chain. The U.S. takes a decentralized and privatized approach, in which pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) negotiate reimbursement terms with pharmaceutical manufacturers and pharmacies. Plan sponsors, public and private payers who offer health benefits, including prescription drug coverage, contract with PBMs for access to these rates.

PBMs have historically been viewed as effective in constraining costs by popularizing generic drugs and using formularies to negotiate brand-name drug rebates for plan sponsors. The forerunners of modern PBMs began to negotiate reimbursement rates with pharmacies in the 1950s, offering health plans sponsored by unions and employers access to these negotiated rates. Over time, their capabilities expanded to include processing claims and negotiating directly with pharmaceutical companies.

As PBMs gained traction, their role also became embedded in statutes regulating medical insurance. Their role was formalized through the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, which included explicit provisions allowing employer-sponsored health plans to deploy PBM offerings to control costs. Legislative changes, such as the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act (MMA), further solidified their role as intermediaries between health plan sponsors, pharmaceutical companies, and pharmacies. Even when Medicare gained the authority to negotiate for certain drugs under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, Congress maintained the use of PBMs to manage the costs of most prescriptions.

But legislative support for PBMs has begun to change as public perception of PBMs has shifted. Rising drug prices and out of pocket (OOP) payments, opaque contracts, and alleged conflicts of interest and anti- competitive behavior have prompted scrutiny of PBM business practices. These concerns coincide with significant consolidation and vertical integration in the industry. Today, three PBMs manage prescription drug claims for around 80% of the U.S. market, with approximately 70% of Americans covered by a health insurance plan that is vertically integrated with a PBM.

Proponents of reform posit that this degree of concentration leads to higher drug prices at the expense of plan sponsors, consumers, and government. But their economic scale has an important advantage. PBMs provide a counterweight to pharmaceutical companies’ market power and are effective at ensuring that pharmacy access remains affordable; their negotiations can save health plans and their beneficiaries a significant amount of money. Indeed, pharmaceutical manufacturers and pharmacies have an inherent interest in reducing PBMs negotiating power and are among the most vocal advocates for their reform.

Still, supply chain complaints are not so easily dismissed given recent calls for reform from employer sponsors of health plans and some consumer groups. Commercial health plans cover more than 50% of Americans, and many believe that PBMs’ market power and vertical integration allows them to act in self-interest at the expense of their clients. Meanwhile, consumers see little direct benefit from PBM negotiations with drug makers, because their insurers base patient cost-sharing at the pharmacy counter on drug list prices, which are not discounted by any rebates a PBM might have negotiated.

Disparate motivations aside, this coalition of interests has gained significant political traction and the issue of PBM reform has emerged as one of few areas with bipartisan agreement. Various proposals have advanced through the House Committee on Energy and Commerce (E&C), the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability (Oversight), the Senate Committee on Finance (Finance), the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP), and the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation (Commerce). Table 1 summarizes each of these proposals along four key areas:

Regulating revenues by restricting PBM compensation from rebates

Regulating revenues by restricting PBM use of spread pricing

Creating accountability to plan sponsors

Requiring studies of vertical integration

(See Appendix for provision-specific details.)

Table 1. Areas of PBM Reform by Congressional Committee

Commercial plans refers to group plans sponsored by employers, unions, and associations, as well as non-group plans that purchased individually by consumers

Areas of concern

PBM Revenues from Rebates and Spread Pricing

All major legislative packages include provisions to regulate PBM revenues. These proposals seek to resolve a common plan sponsor complaint that PBMs retain more than their fair share of rebates and don’t pass through the lowest possible prices at the pharmacy counter. Consumer advocates point to another issue: both forms of revenue contribute to higher OOP costs.

Rebates Explained

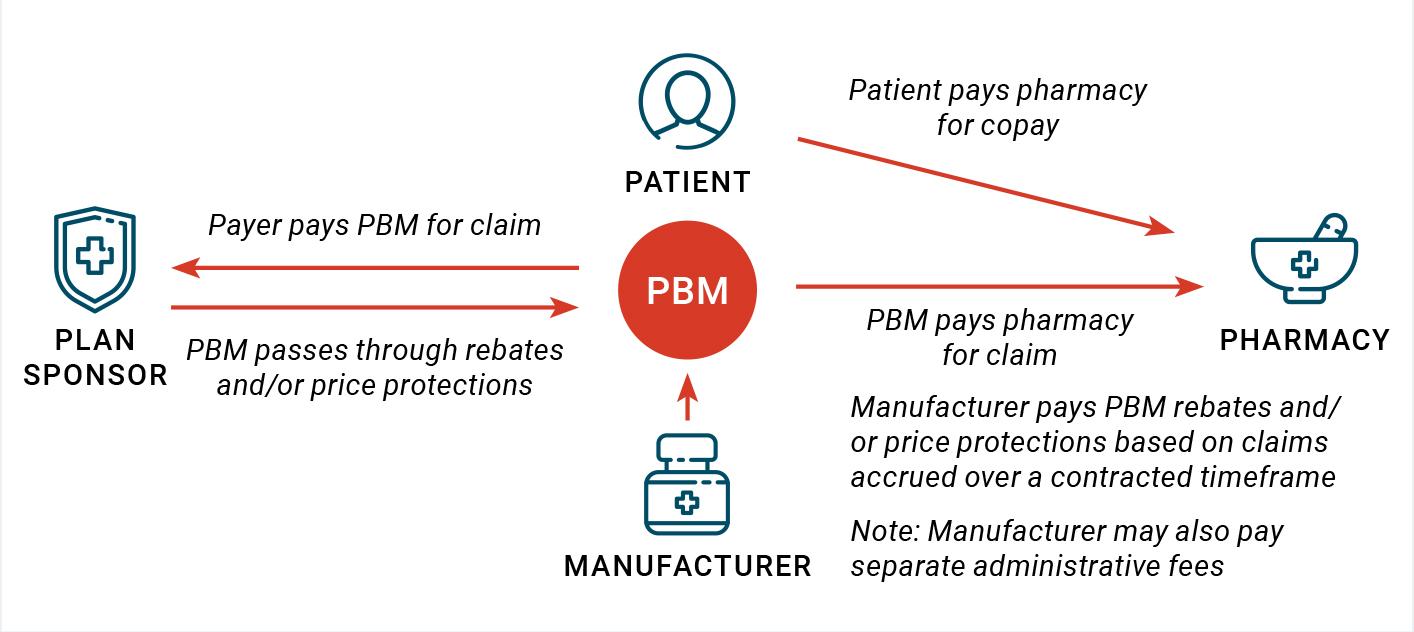

PBMs negotiate with manufacturers for placement of their drugs on health plans’ formularies. In therapeutic classes with a significant amount of competition, manufacturers often pay rebates in exchange for placement on a formulary tier that has fewer access restrictions to patients. Rebates may also be conditioned on volume of sales or market share achieved, with higher levels triggering higher rebate percentages. PBMs collect rebates from manufacturers based on their performance against these contracts over a period of time. Depending on terms negotiated with their plan sponsor clients, PBMs then pass some or all of these rebates through to plan sponsors.

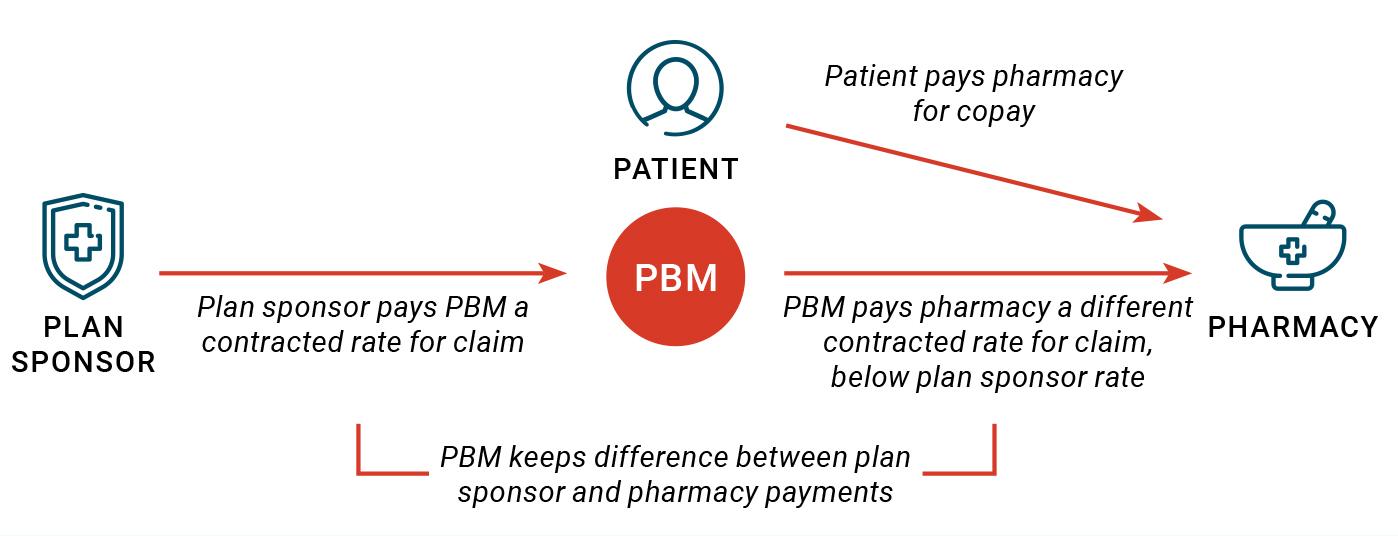

PBMs obtain rebates from drug makers in exchange for preferring brand-name drugs, which encourages manufacturers to set higher list prices (see Rebates Explained). Another rebate is generated when PBMs charge plan sponsors more than what they pay pharmacies to dispense them, a practice known as spread pricing (see Spread Pricing Explained). Because OOP costs are determined by list prices, they increase as well. Spread pricing contributes to similar affordability issues, since OOP costs are based on the higher rate paid by plan sponsors rather than the lower rate PBMs pay pharmacies.

Spread Pricing Explained

Spread pricing refers to the difference between what PBMs pay pharmacies and what plan sponsors pay PBMs for dispensing a drug. This can happen when plan sponsors agree to pay PBMs pre-specified rates for drugs dispensed to plan beneficiaries but PBMs negotiate a separate pharmacy agreement. Separately, pharmacies enter into agreements with PBMs to participate in their networks. PBMs pay pharmacies based on the rates set forth in these network agreements, which may be lower than those in agreements with plan sponsors. In these instances, PBMs may keep the difference.

Legislative proposals respond by limiting PBMs ability to retain revenue from these sources. Provisions to limit rebate revenue require PBMs to pass all rebates on to plan sponsors or stipulate that PBMs can only benefit economically from service fees paid by sponsors. Spread pricing is addressed through outright prohibition, requiring that PBMs provide plan sponsors with the lowest possible price at the point of sale (or in the case of several Medicaid provisions, requiring that pharmacies be paid no more than a drug’s average acquisition cost).

Accountability to Plan Sponsors

Most legislative packages propose to increase the accountability of PBMs to plan sponsors. Plan sponsors, especially those in the commercial market, have long voiced complaints that PBMs retain tight control of the information they share, leaving them with little certainty that PBMs comply with their contractual obligations.

To address these concerns, legislative packages take one or both of two approaches: either to guarantee that plans can audit PBMs for performance against their contracts, or to implement “transparency” requirements. Under these requirements, PBMs report to plan sponsors about prescription drug claims, drug acquisition costs and rebates, and other payments from pharmaceutical manufacturers. Some also call for disclosure of net prices to plan beneficiaries.

Plan sponsors, especially those in the commercial market, have long voiced complaints that PBMs retain tight control of the information they share, leaving them with little certainty that PBMs comply with their contractual obligations.

Vertical Integration

Finally, most bills include provisions to study the effects of vertical integration between PBMs and other businesses in related healthcare sectors. The three largest PBMs — Express Scripts, Optum, and Caremark— serve approximately 270 million Americans and are owned by companies that also market health insurance plans as well as retail, mail order, and specialty pharmacy businesses. Proposals to study the effects of vertical integration respond to questions about whether common ownership is at odds with the interests of plan sponsors, beneficiaries, and other supply chain participants.

One concern is that vertical integration between health insurers, pharmacies, and PBMs coincides with increasing concentration in these markets. In highly competitive markets, cost efficiencies from vertical integration are shared with consumers. For plan sponsors and beneficiaries, this would mean lower premiums and OOP costs because PBMs would compete by sharing more of their rebate revenues and offering lower prices at pharmacies. In fact, in a highly competitive market, reforms to regulate revenues and increase accountability would be redundant.

But vertically integrated businesses with significant market power don’t have to share as much of their cost efficiencies. For plan sponsors and beneficiaries, this means increased health insurance premiums and OOP costs. Accountability provisions, including transparency and audit requirements, are unlikely to improve matters when higher premiums are a result of PBMs greater market power, not non-compliance with contract terms.

Vertical integration also creates opportunities to foreclose competition from rivals by raising their costs or reducing their access to customers. For instance, acquiring the dominant maker of a critical input for a particular product allows the acquiring firm to increase the price of that input to its rivals, making them less competitive. Businesses under common ownership with PBMs have come under increasing scrutiny for behavior in this vein. In one example, a study found that Part D premiums of unaffiliated plan sponsors grew after a large insurer and PBM merged. Independent pharmacies also assert that PBMs give their own pharmacies better payment terms and steer patients with the most profitable prescriptions to them.

However, stakeholder assertions have yet to be backed by clear evidence that vertical integration has resulted in anti-competitive behavior. To address this gap, several provisions call on federal agencies to examine payments to affiliated and competitor entities. Some call for assessments of the effects of common ownership on pharmacy networks and health plan offerings, and at least one (E&C) is to examine the effects of vertical integration on beneficiaries.

Areas of Concern by Plan Sponsor Type

Despite sharing common aims, the packages vary in how they respond to underlying concerns, with potentially significant consequences. This is because PBMs serve multiple markets, each with distinct laws and regulations shaping revenue opportunities and incentives. Plan sponsors, the entities who take on risk as part of offering the benefit, also vary by market and spending levels. As of 2017, commercial health plans accounted for 42% of total U.S. prescription drug spending, while Medicare Part D and Medicaid contributed 30% and 10%, respectively.

Table 2. Main Markets for PBM Services

ACA = Affordable Care Act

MA-PD = Medicare Advantage plan with Part D component

Because rules governing PBM services are specific to each market, policymakers cannot make one-size- fits-all assumptions about these underlying issues. Evidence from one market may not apply to another; each requires its own evaluation.

Medicare Part D

In Medicare Part D, evidence suggests that most rebates are shared with plan sponsors. Oversight studies have shown that all but 1% of rebates are passed through to plan sponsors, and that most PBM compensation takes the form of service fees. This may be because plan sponsors must factor rebates into premiums and beneficiary cost-sharing.

Spread pricing has also been of limited concern in recent years. This may be because differences between plan sponsor payments to PBMs and PBM payments to pharmacies must be reported to CMS, and patient cost sharing must be based on the lower amount. Nevertheless, a recent empirical analysis suggests that it may still occur in some instances.

Although the high rate of rebate sharing between PBMs and plan sponsors is often attributed to these rules, a lack of competitive pressure likely also plays a significant role. The majority of Part D beneficiaries are enrolled in plans sponsored by health insurers under common ownership with a PBM. Enrollment in vertically integrated Medicare Advantage plans appears similarly concentrated. Common ownership aligns PBMs with plan sponsor interests, since revenues go towards the same bottom line. This suggests that accountability measures are unlikely to have a major impact. The degree of market concentration and vertical integration also implies that beneficiaries are unlikely to get the best deal on premiums or cost-sharing.

Medicaid

In Medicaid, sharing of rebates is not a major concern, since they are in most part collected by the federal government and states rather than health plans or PBMs.

Spread pricing, however, has emerged as a major point of contention. Several analyses of different state Medicaid programs have identified instances in which PBMs appear to systematically benefit from spread pricing in their contracts with Medicaid MCOs. Systematic overpayment inflates capitated rates paid to MCOs. With more than 70% of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in such plans, the cost burden to federal and state programs can be significant. For example, a 2018 investigation by Ohio’s state auditor found that spread pricing in Medicaid managed care amounted to nearly $225 million over a one-year period. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) has been studying this issue, with a report expected this year.

For Medicaid, accountability measures center on the issue of spread pricing, particularly with respect to MCOs administering benefits. Several states have already passed laws banning spread pricing or requiring that PBMs pay pharmacies no less than the average acquisition cost of a drug or report information to the state.

Commercial Health Plans

In recent surveys of employer-sponsored health plans, 42-46% reported that their contracts guarantee pass-through of 100% of rebates; others reported partial pass through or guaranteed flat amounts. Meanwhile, a 2018 study found that PBMs retain less than 5% of gross profits from prescription drugs reported by supply chain entities.

Both rebate sharing and spread pricing have become concerns in the market for commercial health plans, particularly for employers who offer group plans. Employers contend that PBMs do not share all of the rebates they negotiate on sponsors’ behalf. PBMs counter that they pass through more than 90% of rebates. In recent surveys of employer- sponsored health plans, 42-46% reported that their contracts guarantee pass-through of 100% of rebates; others reported partial pass through or guaranteed flat amounts. Meanwhile, a 2018 study found that PBMs retain less than 5% of gross profits from prescription drugs reported by supply chain entities.

In the absence of clear evidence, economic theory may offer some insight. Allowing PBMs to retain some rebate revenue aligns their financial incentives with their clients’ interests. Models show that these incentives can make PBMs quite effective at negotiating net price concessions; however, the degree to which these savings are shared with plan clients depends on how intensely PBMs compete. The more concentrated the market, the less pressure to pass all rebates through to plan sponsor clients. One analysis of commercial plan offerings shows a high level of concentration across most regional markets, albeit with some amount of variation. Markets for employer-sponsored plans have become more concentrated in recent years.

Evaluating the extent of spread pricing in the commercial market is also difficult. Few, if any, estimates are publicly available. There is no doubt that the practice exists, since PBMs themselves describe it as a way of taking on risk for outlier reimbursements while providing plan sponsors predictable costs at the pharmacy counter. In a 2023 survey, 71% of employer and commercial health plan sponsors reported that their PBM contracts called for pass-through pricing at the pharmacy. However, evidence for both the variability in payment rates and the financial benefits of addressing it, is limited.

Expert opinions on the role of spread pricing in the employer-sponsored commercial market are mixed. Some actuaries observe that plan sponsors can save more under contracts that allow for spread pricing rather than passing through negotiated rates, since the revenue opportunity from spread pricing serves as an incentive for PBMs to encourage generic substitution. However, as with rebates, significant market concentration raises questions about whether commercial plan sponsors have a choice between contracts with and without spread pricing, and whether competition among health insurers and PBMs truly offers them the best deal.

The process by which employers procure PBM services may contribute to these concerns. When choosing a PBM to administer pharmacy benefits, plan sponsors issue requests for proposals (RFPs) often administered by third-party benefits consultants. PBMs commonly respond to RFPs with bids that specify discount guarantees from average wholesale prices (AWP) for three groups of drugs — generics, brands, and specialty — as well as reimbursement rates to retail and mail order pharmacies. Categorizing drugs into these three groups is often left up to the PBM unless the plan sponsor or their benefits consultant requires specific lists in their RFPs. Plan sponsors then select from among the submitted proposals, the terms of which shape the contract. There are few rules to ensure plan sponsors can compare PBM bids on an apples-to-apples basis.

This leaves employers with two main tools to ensure that PBMs are performing according to contract. One is to hire a third-party to audit their PBM’s performance against contract terms. Although some states have moved to guarantee plan sponsors’ right to audit, this is not typically granted automatically; instead, plan sponsors negotiate these terms with PBMs during the RFP and contracting process. Plan sponsors may then retain third-party auditors to compare their prescription drug claims and rebate guarantees under these terms. Demanding and exercising audit rights requires market power and resources on the part of commercial plan sponsors, leaving this tool available primarily to large employers.

The other tool is threatening to switch to another PBM when the contract expires. Although this is something even small employers can do, it requires a choice between different PBMs, as well as skills and resources to develop an RFP that gives a fair basis for comparison. In addition, PBMs may be relatively insensitive to threats of non-renewal, particularly from small employers.

Vertical integration heightens concerns about competition for employer sponsor business. Nationally, large insurers under common ownership with PBMs are responsible for approximately 90% of rebate negotiations on behalf of commercial plans that cover both medical and pharmacy benefits, disadvantaging employers and individuals who must purchase health coverage in highly concentrated markets. Employers may have the option to “carve out” their pharmacy benefit, assigning it to a different PBM which can encourage some competition. Approximately 40% of people covered by commercial health insurance have pharmacy benefits managed by a different entity than their medical benefit.

Are Reform Proposals Fit for Purpose?

As currently proposed, the extent to which reforms will live up to their promise depends on whether they can be enforced while preserving PBMs’ ability and incentives to negotiate with counterparties. These details are particularly important for provisions regulating how PBMs make money.

Regulating Revenues by Restricting PBM Revenues from Rebates and Use of Spread Pricing

Policies to regulate rebate revenues and spread pricing would most likely have an impact where plan sponsors are not vertically integrated with PBMs; that is, the market for employer-sponsored health plans and Medicaid.

Policies to regulate rebate revenues and spread pricing would most likely have an impact where plan sponsors are not vertically integrated with PBMs; that is, the market for employer-sponsored health plans and Medicaid. HELP, Oversight, and Commerce bills contain policies to this end, while the House E&C bill aims to prevent PBMs from benefiting from spread pricing under Medicaid and for commercial health plans.

Removing rebates and spread pricing as a source of income for PBMs implies compensation through service fees. There is some appeal to this approach, but there are at least two arguments against the proposed restrictions. One is that allowing PBMs to keep a share of the gains encourages them to get better deals from pharmaceutical manufacturers and pharmacies. Removing these revenue opportunities could leave PBMs less motivated to act on behalf of their plan sponsors relative to their supply chain counterparties.

The other argument is that revenue regulation will be ineffective if vertical integration allows PBMs to reconfigure their contracting and accounting practices. For example, PBMs could reclassify rebates from manufacturers or discounts from pharmacies as other types of remuneration or contract terms. PBMs enter into contracts with manufacturers for handling access to their drugs; these contracts include administrative fees that are commonly based on a percentage of drug’s list prices and not necessarily passed through to plan sponsor clients.

Such contracts could allow rebates to be reclassified as fees, avoiding the intent of the legislation. They also have another downside: like rebates, conditioning service fees on drug prices aligns PBMs’ incentives with high-priced drug, potentially leaving current proposals incomplete.

In other words: at least two things are necessary for current provisions to be effective at lowering prescription drug costs and ensuring that PBMs are aligned with their purchaser clients’ interests. First, requirements constraining PBM compensation must apply to all PBM income from manufacturers and pharmacies, not only to rebates and pharmacy reimbursement rates. Second, these terms must be enforceable.

Creating Accountability to Plan Sponsors

Current legislative packages assign enforcement of revenue regulations to plan sponsors, federal agencies, or both. The SFC bill affirms Part D plans’ right to audit their PBMs, while Commerce provisions require PBMs to provide data on spread pricing and pharmacy price concessions to the FTC. E&C’s proposal requires PBMs to report net drug prices and acquisition costs, and to provide plan sponsor data and information about third- party payments to plan sponsors’ fiduciaries. HELP legislation contains similar provisions, also requiring that PBMs allow plan sponsors to see their contracts with rebate aggregators and pharmaceutical manufacturers. One proposal, from E&C, requires disclosure of net prices to plan beneficiaries.

As a practical matter, more information does not necessarily translate to greater accountability or lower costs. Some plan sponsors already audit PBM performance, and a number of large employers require PBMs to disclose certain third-party contracts and aggregate rebate information. But not all plan sponsors have the market power to demand these terms or the resources to act on them.

While current provisions give commercial plan sponsors more rights, they still need to engage a third-party auditor at their own expense. In 2023, employers offered more than 74,000 health plans; processing audits for even a subset of these plans would create significant overhead costs. PBMs have the market power to pass these costs back to plan sponsors through higher premiums. Smaller plan sponsors may also find that they cannot afford to audit or enforce compliance. Without a credible threat of discovery and meaningful penalties, PBMs not acting in plan sponsors’ interests would have little incentive to change their behavior.

In the case of spread pricing, the volume of data alone may be staggering, with more than 60,000 pharmacies operating and contracting with PBMs in the United States today.

Reliance on disclosure is another drawback of many provisions, because they may prove difficult and costly to implement. In the case of spread pricing, the volume of data alone may be staggering, with more than 60,000 pharmacies operating and contracting with PBMs in the United States today. Although pharmacy services administrative organizations (PSAOs) negotiate collectively for some of these pharmacies and others are members of retail chains, the number of contracts and payment terms create real challenges for data collection and analysis, let alone enforcement at an affordable cost.

Another issue is that greater access to pricing data can have unintended consequences. In markets with many competitors, unfettered access to information can give individual consumers the ability to select the lowest cost option. In highly consolidated markets, however, competitors can use publicly available information to tacitly collude by coordinating their pricing decisions. For branded prescription drugs, which compete head-to-head with just a handful of other treatment options, giving pharmaceutical manufacturers price information could lead to less competition on rebates and higher net prices. Likewise, pharmacies in certain markets might also be able to coordinate their pricing with more information. (Although most pharmaceutical companies and pharmacies have access to some competitive pricing intelligence today, it does not rival the comprehensive data implied by Congressional proposals.)

Finally, the degree of vertical integration among PBMs and other entities raises questions about whether even fully enforced accountability provisions are enough to enforce revenue regulations. For example, data sharing requirements for commercial health plans would be meaningless if PBMs changed the classification of revenues from rebates and spread pricing, allocating them to other subsidiaries under the same corporate umbrella.

Preliminary evidence from vertically integrated Medicare Advantage plans suggests that common ownership creates ways to avoid rate regulations. For Medicare and in the individual plan market, vertical integration creates a related issue: common ownership aligns the financial incentives of Part D plan sponsors with their PBM, while a high degree of concentration in the market may contribute to a lack of competitive pressure. Transparency requirements might reveal non-compliance with contracts, but don’t increase competition or prevent foreclosure of unaffiliated rivals.

Requiring Studies of Vertical Integration

Vertical integration clearly poses challenges for the implementation of revenue regulation and accountability measures. Because the nature of that challenge varies by plan sponsor type, studies to examine the effects of common ownership need to be specific to each market.

In Medicare Part D and Medicare Advantage, vertical integration has diminished the distinction between plan sponsors and PBMs. These entities already share revenues, muting the impact of accountability measures. A critical question for this market is whether competition in the program is sufficient to guarantee beneficiaries the lowest possible premiums.

Unlike Part D plan sponsors, the vast majority of employer sponsors in the commercial market are not integrated with their PBM. Many are disadvantaged by their size relative to health insurance companies, PBMs, and affiliated business interests. For employers, the critical question is whether health plan and PBM competition are enough to provide them access to better deals if they have the information and audit rights to demand them. While most markets for employer benefits are highly concentrated, the ability to carve out the pharmacy benefit gives sponsors an opportunity to shop around. This emergence of smaller, unaffiliated PBMs may also offer more choice. However, the extent to which these choices are actionable is unclear.

Another question is whether integrated PBMs and affiliated businesses are acting to foreclose on their unintegrated rivals across markets, reducing competition among health plans and pharmacies. Although studies have shown premium increases after vertical integration in some markets, systematic evidence of anti-competitive behavior of PBMs in the health insurance and pharmacy market is scant. This could be because the health insurance market is fragmented, and circumstances suggesting anti-competitive behavior would be highly specific to each market. It is also possible that allegations of anti-competitive behavior are a response to the lack of transparency in the PBM market, rather than stakeholder knowledge to support any specific theory of harm.

Studies examining whether vertical integration benefits plan sponsors and beneficiaries are needed to fill each of these evidence gaps. Designed well, research reports to Congress can offer significant insight on distortionary incentives and prompt legislative action, including in response to concerns about competition. For example, in 1989, GAO issued a report to Congress on physician patterns of referral to healthcare businesses they owned, finding that physicians with ownership interests in clinical laboratories referred more patients to testing than did their non-owner peers, driving up utilization of tests and healthcare costs. These findings led Congress to pass what are now known as “Stark Laws” prohibiting physician self-referral.

Still, there is no guarantee that currently proposed studies of vertical integration will produce evidence to inform effective policymaking. Several packages, including E&C and HELP, place substantial emphasis on evaluating the pharmacy market. However, they limit their attention to competition in the market for health insurance, perpetuating an evidence gap that may become critical to the success of revenue regulation and accountability policies.

Another concern is that harms from vertical integration can be difficult to establish empirically. For example, companies could selectively stop anti-competitive behavior for the duration of a study, only to begin anew once threat of discovery has passed. Studies focusing purely on anti-competitive conduct run the risk of prompting legislation to ban specific behaviors but keeping the underlying incentive intact.

Finally, most proposed studies are not adequately funded. Lawmakers provide dedicated funding for some studies but not others, which burdens the agencies tasked with executing substantial scopes of work. For example, the E&C bill puts $65 million over five years towards the implementation of 10 different price transparency provisions, of which one is a provision for PBM accountability. Many federal agencies, including those already tasked with oversight of healthcare markets, struggle to keep up with growing oversight mandates even as their budgets remain stagnant or have declined.

How Can Proposals Be Improved?

Virtually all Congressional committees with jurisdiction over plan sponsors or PBMs have now passed legislative packages proposing some combination of revenue regulation, accountability measures, and studies of vertical integration. Congress has yet to align on a consensus, but a package that can pass both the House and Senate will almost certainly build from these proposals. As lawmakers consider the ultimate design of PBM reforms, they could consider several adjustments to improve their eventual impact.

All proposed packages include reforms limiting PBMs’ ability to benefit from rebates and spread pricing. These provisions risk reducing their effectiveness as negotiators within the supply chain, which could ultimately lead to higher drug prices and spending. To employers and other plan sponsors who are not integrated with a PBM, this may be a moot point. The more concentrated the market for PBM offerings, the less likely unaffiliated plan sponsors are to share in the full benefit of PBMs negotiations.

These provisions risk reducing their effectiveness as negotiators within the supply chain, which could ultimately lead to higher drug prices and spending. To employers and other plan sponsors who are not integrated with a PBM, this may be a moot point. The more concentrated the market for PBM offerings, the less likely unaffiliated plan sponsors are to share in the full benefit of PBMs negotiations.

This tension is frequently found among public utilities, where the justification for allowing monopolies is their cost efficiency. PBMs are not monopolies however, which means that Congress can draw on other options to maintain their effectiveness as negotiators, such as encouraging more competition.

The experience of one federal agency illustrates both why PBMs are needed and why effective PBM contracts require skill and resources.

The Department of Labor (DOL) administers workers compensation benefits for federal employees. Concerns about rapidly growing prescription drug costs in the program, largely due to opioids, prompted an investigation by the OIG. That inquiry found that the agency had no PBM and failed to take actions that traditionally fall to a PBM, such as controlling access to restricted medications and negotiating for better net prices. Options included hiring a PBM, and in 2018 DOL began the process of finding one. But a follow-up investigation was critical of DOL’s subsequent choice, finding that the agency’s contract with the selected PBM was not competitive. Among other things, the report concluded that the agency had failed to vet the PBM’s offering to make sure it was getting the best deal on drug prices.

Option 1: Use Competition In Related Markets to Create a Public Benchmark

One way to avoid overpaying PBMs is to take advantage of competition in related markets. Provisions to address spread pricing in Medicaid do this by requiring pharmacies be reimbursed at no more than the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC).

NADAC is already publicly available, but these bills also require that pharmacies respond to NADAC surveys, which will improve accuracy. While this may raise administrative costs to pharmacies, impacts on plans and consumers are likely to remain minimal because pharmacies are relatively competitive.

There is value in having an accurate public benchmark: because pharmacies negotiate what they pay for drugs to wholesalers and compete with one another for business, their acquisition costs offer important information against which to gauge PBM reimbursement of pharmacies. Although this provision is intended to save Medicaid programs money, a public benchmark price in a competitive market benefits other plan sponsors as well.

Option 2: Standardize RFPs for PBM Services In the Commercial Market

In the market for employer-sponsored pharmacy benefits, PBMs have the advantage of a relatively complex procurement process that allows them to submit bids on differing terms. This limits how intensely PBMs have to compete, since plan sponsors are limited in their ability to compare one bid with another.

Requiring that bids allow for apples-to-apples comparisons improves plan sponsors’ ability to identify the most competitive offering.

To encourage more competition, lawmakers could require that PBM responses to employer RFPs all follow the same list of generic, branded, and specialty drugs. Such a list could be supplied by HHS, benefits consultants, or plan sponsors themselves. Requiring that bids allow for apples-to-apples comparisons improves plan sponsors’ ability to identify the most competitive offering.

Option 3: Allow Commercial Market Plan Sponsors to Delegate Audit Rights to a Federal Agency

More competitive bid requirements could be coupled with another adjustment: permitting plan sponsors to delegate oversight of their PBM’s performance to a federal agency, which could audit on their behalf. Federal agencies can be remarkably cost-effective at uncovering fraud and recovering overpayments. Investigations and audits by HHS OIG, which operates on an annual budget of around $500 million, are expected to result in $3.4 billion in recovered costs for FY 2023.

This option builds on current disclosure requirements, with several added benefits. One is that it would streamline the audit process, reducing costs to PBMs and commercial plan sponsors. It would also create a credible threat of discovery and legal action to remedy breaches of contract, and give plan sponsors information to inform future RFPs, increasing competition.

Such an agency program would need to be adequately funded to function effectively. To keep the effort affordable, Congress could allow commercial plan sponsors to pay the agency user fees in exchange for the oversight, which would almost certainly be cheaper for sponsors than conducting their own oversight.

Option 4: Protect Emerging PBMs from Foreclosure

Congress can also do more to foster PBM competition. PBMs promising transparent business models that have emerged in recent years may offer this opportunity. Most don’t negotiate their own contracts with pharmaceutical manufacturers. Instead, they obtain rebates through rebate aggregators run by the three largest PBMs. To prevent foreclosure of these would-be rivals, Congress can be explicitly include PBM’s rebate aggregator businesses and contracts with PBM competitors in currently proposed study and transparency requirements.

Option 5: Increase Priority of Studying Vertical integration between PBMs and Health Plans

While policies to improve PBM competition may improve their performance for non-affiliated plan sponsors, the same does not hold true when plan sponsors and PBMs are vertically integrated. This is the case for the many plan offerings in Medicare Part D and Medicare Advantage.

Vertical integration creates opportunities to avoid revenue regulations and blunts the impact of accountability measures. For these provisions to have an impact, the role of vertical integration in avoiding them must be addressed. To date, lawmakers have declined to presume that the anticompetitive effects of vertical integration among health plans and PBMs outweigh its potential efficiencies. In the absence of a presumption or strong evidence in one direction or another, prioritizing studies to understand the tradeoff can help Congress to anticipate and shape the impact of multiple provisions hanging in the balance.

Option 6: Commit Adequate Resources and Refine the Scope of Vertical Integration Studies

Several legislative proposals include extensive requirements for federal agencies to study vertical integration, but do not provide commensurate funding. Lawmakers can ensure that the demands of these studies don’t inadvertently force federal agencies to reassign staff and resources dedicated to other important oversight activities. Congress can do this by increasing funding, or extending the timeline on which agencies are expected to execute on their mandate.

As currently written, studies may focus on specific types of anticompetitive behavior. Market participants can cease specific behaviors while being studied, only to revisit them after scrutiny has passed. When studies do find instances of anticompetitive conduct, it may prompt legislation focused on that behavior, rather than the underlying incentive. Scoping the proposed studies to capture information about incentives could provide additional insight to guide policymaking.

Option 7: Limit Disclosure of Negotiated Prices and Payment Rates

Congress can also prevent accountability provisions from inadvertently sharing information that could be used for tacit collusion. This is important to preserve competition between branded drugs, as well as concentrated regional pharmacy markets. Some proposals already prohibit plan sponsors from sharing information supplied to them by PBMs, which could be adopted in a final legislative package and enhanced with penalties and enforcement.

The greatest concern, however, may be giving consumers direct access to net price information for prescription drugs. Even armed with information, individual consumers do not have the market power to influence PBM behavior or what they pay for prescription drugs. However, access to information at this scale effectively guarantees that it will become public knowledge.

Even armed with information, individual consumers do not have the market power to influence PBM behavior or what they pay for prescription drugs. However, access to information at this scale effectively guarantees that it will become public knowledge.

Option 8: Safeguard Against Revenue Regulation Avoidance

Revenue regulations focus on two specific forms of income. However, PBMs make money from pharmaceutical manufacturers in other ways as well, such as service fees that are conditioned on the list prices of their drugs. These payments lend themselves to avoidance of revenue regulations, because contracts can be altered to reclassify revenue from rebates into other forms of payment. This would allow PBMs to avoid the intent of revenue regulation. It could also contribute to more problematic incentives, because the explicit quid pro quo of formulary preference in exchange for rebates would be absent in the new arrangements. To avoid this, lawmakers could adopt restrictions already found in some packages, such as Finance, and greater oversight provisions.

Conclusion

Once Congress returns to the topic of PBM reforms, provisions that have already passed committee will serve as the foundation for negotiating a consensus. The revenue regulations at the heart of these provisions make a tradeoff: giving plan sponsors greater assurance that PBMs are meeting their contractual obligations, but risking an increase in prescription drug spending. That burden falls not only to plan sponsors, but to the beneficiaries and patients whose premiums and OOP costs would increase. Our review shows that lawmakers have options to mitigate the downsides of that tradeoff.

In fact, several of these options could be implemented as standalone policies to increase plan sponsor market power without requiring revenue regulation. Although sharpening competition and enforcement mechanisms may seem unpromising in the face of significant concentration and vertical integration, these changes would position plan sponsors and beneficiaries to get more out of possible policy changes in the future, such as FTC or DOJ actions to address vertical integration. Perhaps more importantly, they would encourage PBMs to stay true to their role as the designated negotiators within the prescription drug supply chain.

Appendix

Table 1. Proposed PBM Reforms

Committees of jurisdiction include Energy and Commerce for H.R. 5378, Oversight and Accountability for H.R. 6283, Health, Education, Labor and Pensions for S. 1339, and Commerce, Science and Transportation for S. 127.

Commercial plans refers to group plans sponsored by employers, unions, and associations, as well as non-group plans that are purchased individually by consumers.

FTC = Federal Trade Commission GAO = Government Accountability Office MA = Medicare Advantage MCO = Managed Care Organization PDP = Medicare Part D Plan SFC = Senate Committee on Finance

ABOUT ATI ADVISORY

ATI Advisory is a healthcare research and advisory services firm dedicated to system reform that improves health outcomes and makes care easier for everyone. ATI guides public and private leaders in developing scalable solutions. Its nationally recognized experts apply the highest standards in research and advisory services along with deep expertise to generate new ideas, solve hard problems, and reduce uncertainty in a rapidly changing healthcare landscape.

Learn more at atiadvisory.com

Follow @ATIAdvisory

ABOUT WEST HEALTH

Solely funded by philanthropists Gary and Mary West, West Health is a family of nonprofit and nonpartisan organizations, including the Gary and Mary West Foundation and Gary and Mary West Health Institute in San Diego and the Gary and Mary West Health Policy Center in Washington, D.C.. West Health is dedicated to lowering healthcare costs to enable seniors to successfully age in places with access to high- quality, affordable health and support services that preserve and protect their dignity, quality of life and independence.

Learn more at westhealth.org

Follow @WestHealth

Downloads

ATI-PBM-Paper_4.15.24.pdf

Download