Addressing Cognitive Decline in a Diverse Aging Population

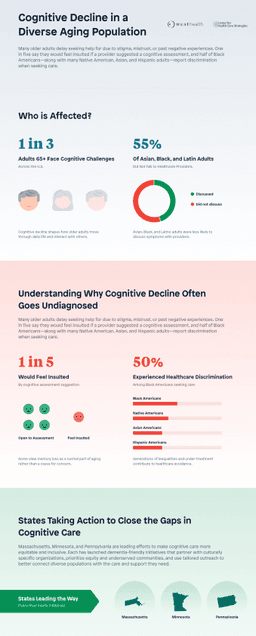

August 14, 2025Cognitive decline affects nearly one-third of adults age 65 and older across the U.S., shaping how they move through daily life, interact with others, and navigate the healthcare system. While cognitive changes can be a normal part of aging, the experience is far from universal. For older adults from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups, cognitive decline is compounded by systemic inequities and limited access to care, which effects quality of life and contributes to higher rates dementia and Alzheimer's, and worse outcomes.

The Alzheimer’s Association found that while White people are the majority of those with Alzheimer’s in the U.S., Black and Hispanics adults face higher risks. Black Americans are twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s and other dementias, and Hispanics face one and a half times the risk. They are also typically diagnosed much later and as a result need more services and incur higher costs for treatment.

Additional research shows Black women have the highest age-standardized risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Research also shows that Asian Americans are at high-risk for under-detection of cognitive impairment.

The rate of cognitive difficulty, meaning difficulty remembering, concentrating or making decisions due to a physical, mental or emotional condition, rises from 9% among those age 65 or older to nearly 20% among those 80 or older.

While cognitive decline is widespread, not everyone experiences it in the same way or gets the same opportunity for care. Using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found of the adults over age 50 who reported increased confusion or memory loss in the past year, Asians, Black, and Latino adults were less likely to have initiated a discussion about their symptoms with their health care provider.

Because discussing changes in cognition can help with prevention, early detection of more serious conditions, and developing care plans, it is important to understand why these conversations between older adults of color and their providers happen less frequently. This highlights why other factors should be considered to help improve outcomes and reduce racial and ethnic disparities related to cognitive decline.

Among people reporting more frequent or worsening confusion or memory loss in the past year, nearly half (45%) said they talked about their cognitive decline with a healthcare professional.

What Prevents Older Black and Hispanic Adults from Talking about Cognitive Decline

The reasons older adults may avoid sharing concerns about confusion or memory loss with their healthcare providers are complex and are shaped by their lived experiences. Some view memory loss as a normal part of aging rather than a cause for concern and would not seek treatment. Others may not talk openly about cognitive or mental health declines due to stigma, shame or pride or that it may be a sign of personal weakness, which can lead to delays in treatment or total care avoidance. According to a 2021 Alzheimer's Association report, one in five Black and Hispanic Americans reported that they would “feel insulted if a doctor suggested a cognitive assessment.”

Other barriers include limitations in awareness and understanding of cognitive health, language and cultural challenges, and limited interactions and time with healthcare providers. For historically marginalized groups, their experience is also shaped by a lifetime of discrimination that goes beyond the doctor’s office. Many have longstanding mistrust in the healthcare system, fueled by generations of systemic racism and under-treatment, which often leads individuals to avoid bringing up concerns they fear will be dismissed or misunderstood.

Half of Black Americans, more than 40% of Native Americans, and about one-third of Asian Americans and one-third of Hispanic Americans indicate they experienced discrimination when seeking care.

62% of Black Americans believed that clinical trials were biased against non-White Americans.

47% of Black Americans distrusted that future advancements in treatments would be shared equally.

Non-White Americans were not confident they would have access to culturally competent providers who understands their needs.

Source: 2021 Alzheimer's Association

Opportunities for Supporting Older Adults Experiencing Cognitive Decline

Gaps in communication and lapses in care have serious consequences. For healthcare systems that rely on self-reported symptoms to initiate screening and referrals, this can delay diagnosis and limit care options. And for families, a lack of timely support often means navigating complex, progressive conditions through an equally complicated healthcare system without adequate resources or guidance.

Providers, policymakers, and community-based organizations can take steps to support earlier identification and more equitable care through:

Implementing initiatives focused on culturally competent care.

Culturally tailored care models and services. Embedding dementia education in trusted spaces, such as faith-based organizations or community centers, can help reduce stigma and increase early screening. Lessons can be drawn from initiatives focused on other chronic conditions, such as culturally-tailored diabetes prevention programs that improve diagnoses and health outcomes.

Culturally competent workforce. Increasing diversity among healthcare providers as well as ensuring both clinicians and staff receive training in culturally responsive care can improve trust and communication. Older adults are more likely to feel heard and understood when their care team reflects their values, language, and lived experience.

Leveraging existing models and frameworks. Initiatives, like the IHI Age-Friendly Health Systems Framework (the 4Ms) and Medicare’s Annual Wellness Visit (AWV) requirement, support early identification of cognitive decline and can help with advancing health equity. A limitation of the AWV is that utilization has been low though some research has shown an increase in detection among Black Americans.

Redesigning assessment tools. Standard cognitive screening tools may not account for differences in language, education, or cultures. This creates an opportunity for new assessment tools to be developed that are linguistically appropriate, culturally relevant, and tested across diverse populations to help ensure that screenings are accurate and inclusive from the start.

Establishing partnerships through state-level planning efforts, such as Multisector Plans for Aging or dementia-friendly plans. States, such as Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania have all engaged in dementia-friendly initiatives that prioritize equity by partnering with culturally-specific organizations and creating tailored outreach materials and resources that meet the needs of their diverse and underserved communities facing the greatest risks.

Conclusion

With the aging population in the U.S. growing rapidly and becoming increasingly diverse, we will continue to see a rise in the number of people who will experience cognitive health challenges. Implementing strategies and tools that reduce racial and ethnic health disparities will deliver better outcomes and hopefully increase trust in the system.

Downloads

Infographic - Cognitive Decline in a Diverse Aging Population

Download